Alan

Character Report: DR. ALAN WESTFIELD (Dragonfield, Dragon’s Blood)

I. Core Information

- Character Name: Dr. Alan Westfield

- Age: 50s

- Gender Identity & Pronouns: Male (He/Him)

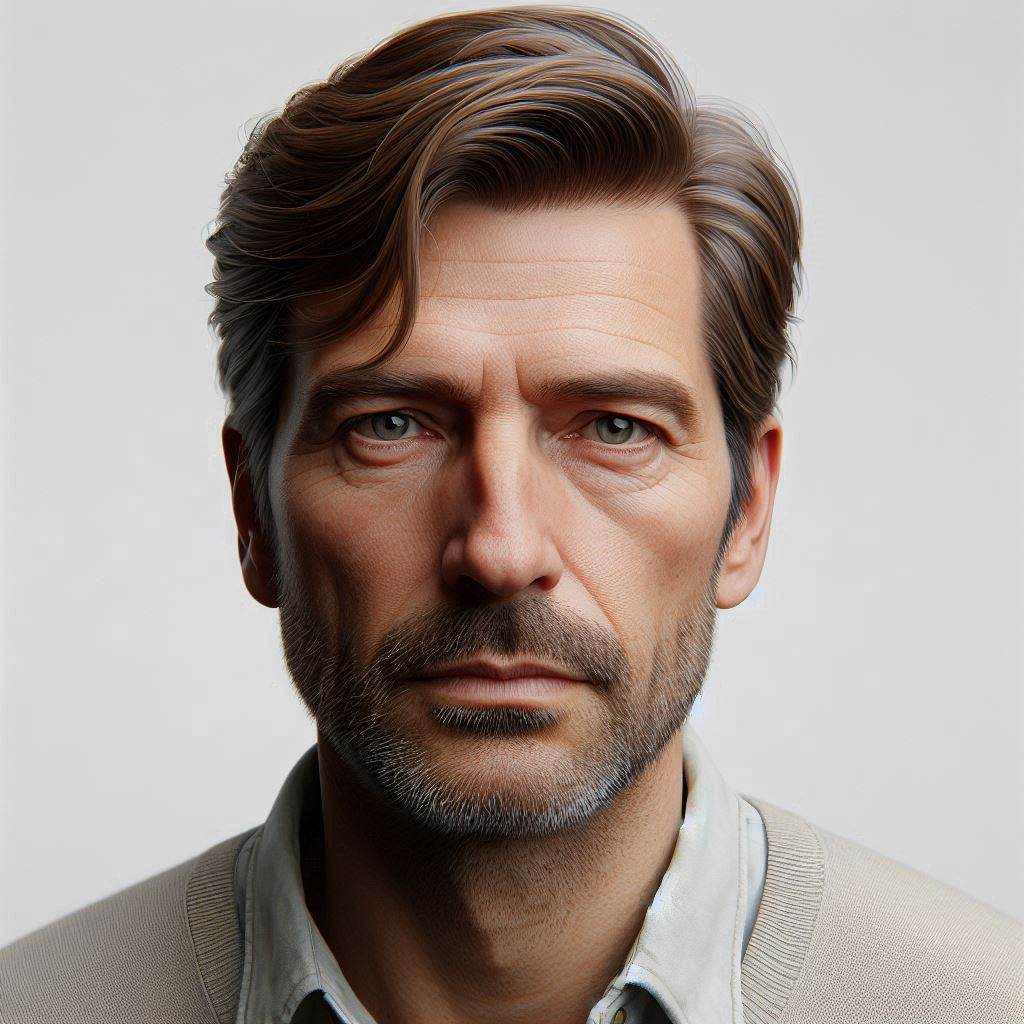

- Physical Description:

- Likely appears professional and somewhat reserved, reflecting his background as a doctor.

- His physical state might show the strain of the unfolding crisis, but he maintains a composed exterior.

- Role in the Story: The patriarch of the immediate Westfield family, a medical doctor, and initially the voice of skepticism and conventionality. He represents the modern, rational world being forced to confront the impossible. He struggles with his past and his role as a father in extraordinary circumstances.

II. Background & History

- Family: Husband to Isabella, father to Ali and Jason. Son of the deceased Baron Atlas Wyrmfeld.

- Profession: A medical doctor, likely with experience in crisis zones (implied by Jason’s reference to “Doctors Without Borders”). This background makes him pragmatic and focused on tangible solutions.

- Estrangement from Father: Had paralyzed his older brother during a jousting accident and a “huge blowout a long time ago” with his father, Atlas, leading him to leave home and change the family name. This past conflict informs his complete rejection of the castle’s legends.

- Modern Mindset: Represents the scientific, rational perspective, initially dismissing the fantastical elements as “madness” or “hoax.”

III. Inner Life & Psychology

- Core Desire/Objective: To protect his family and ensure their safety through conventional, logical means. He desperately wants to regain control and return to a semblance of normalcy.

- Motivation: Paternal love, a strong sense of responsibility, and a deep-seated belief in order and reason. He is driven by the need to find practical solutions and to keep his family together.

- Personality Traits:

- Pragmatic/Rational: Tries to apply logic and scientific understanding to an illogical, supernatural crisis.

- Protective: Deeply cares for his family, though his methods might differ from Isabella’s more visceral approach.

- Skeptical (initially): Dismisses the dragon and legends as “hoax” or “madness.”

- Responsible: Takes charge in a crisis, tries to find solutions (ordering Uber, trying to get to Heathrow).

- Stoic (as per his eulogy for Atlas): Taught by his father to be stoic, suggesting he internalizes stress and tries to maintain a calm exterior.

- Guilt-ridden: Carries the weight of his past estrangement from Atlas and his inability to protect his family from the unfolding chaos. He is no coward, but instinctively leans toward ‘flight’ vs ‘fight’ as he crippled his brother the last time he lost his temper.

- Values & Beliefs: Order, reason, family, and the power of conventional institutions (police, military). He struggles to reconcile these beliefs with the new reality.

- Strengths: Medical knowledge, leadership in conventional crises, a calm demeanor under pressure, and a deep commitment to his family.

- Weaknesses: His reliance on logic and conventional solutions makes him slow to accept the supernatural truth. He struggles with the shame of perceived failure and his past with Atlas. Can be seen as too cautious by his children.

- Secrets: The full details of his “blowout” with Atlas and the emotional weight of that estrangement.

- Temperament: Generally composed and rational, but capable of frustration and despair when his attempts at control fail.

IV. Relationships

- Dr. Maria Isabella Salazar Westfield (Wife): A strong partnership. They rely on each other, but also have moments of friction due to differing approaches to crisis. He respects her fierce protectiveness.

- Alexandra “Ali” Westfield (Daughter): Loves her “daddy’s princess” deeply but struggles to understand her growing connection to the mystical. He might see her as impulsive.

- Jason Westfield (Son): Loves his son, and is proud of his bravery, but also worried by his increasing ruthlessness. He struggles with the guilt of getting separated from him. Their relationship faces strains due to Jason’s rebellion and recklessness.

- Baron Atlas Wyrmfeld (Father, Deceased): A complex, unresolved relationship. Alan’s eulogy hints at both love and past conflict. Atlas’s legacy and warnings now haunt Alan.

- Alois Wintersteller: Initially a figure of authority from his father’s life, Alois becomes a key ally, representing the ancient knowledge Alan initially dismissed.

- Samira & Tanisha: While he agrees to take them, he initially views them as a burden, highlighting his pragmatic focus on his own family’s survival.

V. Arc & Transformation

- Initial State: A rational, modern doctor trying to navigate a family funeral and dismiss his father’s “madness.”

- Catalyst: The dragon’s attack and Jason’s abduction shatter his conventional worldview, forcing him to confront the impossible.

- Pivotal Moments:

- His desperate attempts to get his family to safety via conventional means (airport, Channel Tunnel).

- His struggle to accept the reality of the dragon and the collapse of society.

- His separation from Jason and the subsequent fear for his son.

- His eventual reunion with his children and the realization of the true nature of the threat.

- His confrontation with Isabella about her accusation of him “backing down,” suggesting an internal struggle to assert himself.

- Transformation: Alan transforms from a skeptical, rational man into someone forced to accept the supernatural. He grapples with his past relationship with his father and the limitations of his own worldview. His journey is about learning to adapt, to trust in the unconventional, and to find new forms of strength when all his logical solutions fail. He must confront his own perceived failures and step into a new kind of leadership.

VI. Practical & Miscellaneous

- Voice & Speech Patterns: Clear, educated, often calm and measured, even when stressed. Can be terse or frustrated when his plans are thwarted.

- Physicality: Likely precise and controlled movements, reflecting his medical background. He might show subtle signs of stress (e.g., rubbing his temples, tight posture) as his world unravels.

- Sensory Details: The sterile smell of a hospital contrasted with the smoke and chaos of the outside world. The feeling of helplessness.

- “Animal” Analogy: A grizzled, experienced doctor forced to treat a patient with a disease he doesn’t understand. Or a loyal, but bewildered, sheepdog trying to herd his flock back to safety when the wolves are unlike anything he’s ever encountered.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE

Patient: Dr. Alan Westfield (né Alexander Wyrmfeld)

Age: 50s

Evaluator: [Confidential]

Date: [Current]

Purpose: Character study for performance preparation

PRESENTING BEHAVIORAL PATTERN

Dr. Westfield presents as a highly accomplished, outwardly stable professional whose rigid self-control masks profound unresolved trauma. He exhibits what I term “compensatory life architecture”—an entire adult identity constructed not around authentic self-expression but around preventing repetition of a catastrophic formative event. His passivity, avoidance behaviors, and emotional constriction represent a man living in permanent fear of his own capacity for violence.

INDEX TRAUMA & PSYCHOLOGICAL FRAGMENTATION

The central organizing event of Alan’s psychology occurred at age sixteen: in a moment of uncontrolled rage during martial training, he broke his brother Arthur’s neck, causing permanent paralysis. This was not mere accident—it was the eruption of accumulated fury against a brutal father, a favored brother, and a childhood devoid of mercy or tenderness.

The psychological impact cannot be overstated. In a single moment, Alan discovered he was capable of irrevocable harm to someone he loved. This discovery shattered his nascent identity and created a permanent split: the “before” self who didn’t know he was dangerous, and the “after” self who can never forget it. Every subsequent decision flows from this fracture.

His father’s response compounded the trauma exponentially. Rather than recognizing the accident as the inevitable result of his own brutality, Atlas responded with escalating violence—repeated beatings that transformed legitimate guilt into toxic shame. The message was clear: you are irredeemably bad, dangerously flawed, unfit for human society.

When Alan fled, Atlas systematically destroyed his support network, ensuring the sixteen-year-old had nowhere to turn. This wasn’t discipline—it was psychological warfare designed to break the boy’s will and force capitulation. That Alan survived this without returning “home” demonstrates remarkable resilience, but survival came at enormous cost.

HOMELESSNESS & IDENTITY DISSOLUTION

Alan’s formative years (16-18) were spent in survival mode—merchant marine work, homelessness in Boston, the assumption of a false identity. These experiences occur during critical identity consolidation years. Where most adolescents are exploring who they might become, Alan was simply trying to survive.

The identity change from “Alexander Wyrmfeld” to “Alan Westfield” represents more than practical necessity. It’s psychological dissociation—the creation of a new self untainted by the catastrophic failure of the old self. “Alexander” broke his brother’s neck; “Alan” would never hurt anyone. “Alexander” came from violence; “Alan” built a life of healing. The name change is a rebirth fantasy, an attempt to escape causality itself.

However, dissociation always fails. The traumatized self doesn’t disappear; it merely goes underground, dictating behavior from the shadows. Every choice “Alan” makes is actually “Alexander” trying to prove he’s reformed, trying to earn the forgiveness he can never give himself.

CAREER AS PERPETUAL ATONEMENT

Alan’s choice of neurosurgery—specifically neurosurgery—is not coincidental. He spends his professional life attempting to repair the very injury he caused: spinal and neurological trauma. Every patient whose mobility he restores is a symbolic repair of Arthur. Every successful surgery is evidence that he can heal rather than harm, that his hands can restore rather than destroy.

This transforms his career from vocation into compulsion. He cannot simply be a good doctor; he must be an exceptional one, working harder than any peer, achieving recognition that “proves” his worth. His professional excellence doesn’t reflect passion for medicine—it reflects desperate need for redemption.

The Doctors Without Borders work serves similar psychological function. Isabella believes they volunteer from shared values; Alan participates as ongoing penance. He must perpetually demonstrate that he serves humanity, that he’s not the monster who destroyed his brother. The work is never finished because the guilt is never resolved.

MARRIAGE BUILT ON DECEPTION

Alan’s thirty-year marriage to Isabella rests on a foundational lie. She believes she married an orphan who overcame adversity through determination. She doesn’t know she married a fugitive from patricide-adjacent trauma, a man who reinvented himself to escape his past.

This deception creates profound intimacy dysfunction. True intimacy requires vulnerability and honesty; Alan offers neither. He presents a curated self—successful, stable, loving—while hiding the traumatized core. Isabella loves “Alan Westfield” without knowing “Alexander Wyrmfeld” still exists, making decisions from the shadows.

When cornered about his past, Alan’s response is telling: he raises his voice (losing control he normally maintains), attempts escape (his default trauma response), and minimizes/deflects responsibility even while “confessing.” His statement that he “couldn’t even tell myself” reveals the dissociative mechanism—he’s structured his consciousness to avoid examining the wound.

Critically, even in confession, Alan cannot accept full responsibility. He frames Arthur’s injury as something that “happened” during their father’s “madness” rather than something he did in a moment of rage. This deflection—blaming circumstances rather than owning agency—represents his inability to integrate the shadow self. To admit “I deliberately hurt my brother” would collapse the carefully constructed “Alan” identity.

CONTROL & AVOIDANCE AS PRIMARY DEFENSES

Alan’s personality is organized around one imperative: never lose control again. This manifests in multiple domains:

Alcohol avoidance: Substances that reduce inhibition threaten the rigid self-control maintaining his safety. He cannot risk releasing the rage he knows lurks beneath the surface.

Passive relationship dynamics: By allowing Isabella to dominate household decisions, he ensures he never has to assert himself forcefully. Passivity feels like safety; leadership feels like danger.

Emotional constriction: He maintains tight affect regulation, rarely expressing strong emotion. When he does “put his foot down,” it’s remarkable precisely because it’s rare—and even then, it’s measured assertion rather than authentic anger.

Conflict avoidance: When challenged, his default is retreat. The argument with Isabella about visiting Atlas demonstrates this pattern: he wants to walk away, to ignore the summons, to avoid confrontation. Avoidance has kept him safe for decades; engagement feels existentially threatening.

Selective engagement: Notably, Alan’s only domain of full engagement is patient care. With patients, he can be commanding, decisive, emotionally present—because their lives depend on it, and because medical hierarchy provides structure containing his authority. Outside that framework, he retreats into passivity.

PARENTING AS TRAUMA REENACTMENT PREVENTION

Alan’s dramatically different relationships with his children reflect his core fear: repeating his father’s mistakes.

With Jason: Alan’s emotional absence stems from terror of becoming Atlas. Afraid he’ll be too harsh, demand too much, push too hard, he errs toward complete disengagement. He forbids contact sports not because Jason is fragile but because Alan knows how easily athletic competition can turn violent—he lived it. Every protective prohibition represents Alan preventing the conditions that led to his own catastrophic loss of control.

The tragic irony is that Alan’s avoidance recreates his father’s failure through opposite means. Where Atlas damaged his son through brutal presence, Alan damages Jason through anxious absence. Both fathers fail to provide what their sons need; Atlas couldn’t provide tenderness, Alan can’t provide engagement.

With Alexandra: Ali is emotionally safe for Alan because she doesn’t trigger his core fear. Girls don’t do martial training or contact sports; they can’t break each other’s necks on the jousting field. With Ali, he can be indulgent, affectionate, present—”princess” represents the only child relationship where Alan doesn’t fear himself.

His spoiling of Ali isn’t favoritism in the traditional sense—it’s relief. With her, he can express love without fear, can be generous without anxiety, can parent without triggering trauma associations. She represents proof that he’s capable of healthy parental love, even as Jason represents the relationship he’s too afraid to fully inhabit.

RETURN AS FORCED INTEGRATION

The return to England represents Alan’s worst nightmare: forced confrontation with the dissociated past. Every element he’s avoided for thirty years—the estate, the family name, the barony, the legend, the scene of his crime—becomes unavoidable.

His resistance is proportional to his terror. When he declares “death is near? Good. Let it come”—this isn’t callousness but desperate self-protection. If Atlas dies before Alan arrives, he can maintain the dissociation. If they meet, if they speak, if reconciliation is demanded, “Alan Westfield” must integrate “Alexander Wyrmfeld,” and the carefully constructed life might collapse.

The deathbed confrontation reveals the split: Alan oscillates between rage at abandonment (“you knew where I was… you never lifted a finger”) and confession of his true motive (“I came here to bury you and your legend”). He wants his father’s acknowledgment of wrongdoing while simultaneously denying his own—a psychological stalemate where neither man can accept responsibility, so neither can forgive or be forgiven.

ATLAS AS PSYCHOLOGICAL SHADOW

Alan’s relationship with his father is the defining unresolved conflict of his life. Atlas represents everything Alan fears he might become: violent, controlling, obsessed, demanding. Yet Atlas also represents everything Alan desperately wanted: recognition, approval, belonging, legitimacy.

The complexity lies in Alan’s inability to hold both truths simultaneously. He oscillates between “my father was a monster” and “my father achieved greatness I’ll never match.” He cannot integrate that Atlas was both—a decorated hero and a child abuser, a man of principle and a brutal disciplinarian, someone worth emulating and someone worth escaping.

This splitting means Alan can never resolve the relationship. He cannot grieve properly because he cannot acknowledge what he’s grieving. Is he mourning the loss of the father he had or the father he never had? The man who saved fifty soldiers or the man who destroyed his own sons? The answer is both, but Alan cannot access both.

UNACKNOWLEDGED RAGE

Beneath Alan’s controlled exterior lies the same rage that broke his brother’s neck, completely unprocessed. His entire adult life has been dedicated to suppression rather than integration. He’s never addressed the legitimate fury at his father’s brutality, never processed the rage at Atlas’s post-injury cruelty, never confronted his anger at being erased from his own family.

This suppressed rage occasionally breaks through. His outburst at Isabella about visiting Atlas—”I don’t care what he needs!”—reveals volcanic anger beneath the surface. His confrontation with his unconscious father—”you’re a real son of a bitch… I came here to bury you and your legend”—expresses decades of accumulated fury.

But critically, he never directs this rage at appropriate targets. He doesn’t confront Atlas when conscious. He doesn’t demand accountability. He doesn’t advocate for his own victimization. Instead, he directs anger at those who threaten his defenses—at Isabella for pushing reconciliation, at circumstances for forcing his return. The rage exists but cannot find legitimate expression, so it leaks sideways.

BREAKDOWN & POTENTIAL INTEGRATION

Atlas’s death triggers Alan’s first authentic emotional experience in decades—the moment when his carefully maintained defenses finally collapse. The tears at Arthur’s grave and the breakdown at his father’s deathbed represent not grief alone but the breaking of a thirty-year dam. All the suppressed pain—guilt over Arthur, rage at Atlas, shame about his own weakness, grief over lost family—floods through simultaneously.

This breakdown, while devastating, represents psychological progress. For the first time, “Alan” and “Alexander” exist simultaneously. He’s no longer able to dissociate the past from present, maintain the split between who he was and who he became. The integration is agonizing but necessary.

The final irony: Atlas’s tears suggest mutual recognition of shared failure and shared suffering. Both men were broken by their relationship; both men broke their sons; both men lived with unprocessable guilt and rage. In that moment, they’re not baron and banished son—they’re two damaged men recognizing each other’s pain across an unbridgeable gap.

PERFORMANCE GUIDANCE

For authentic portrayal, the actor must understand that Alan’s entire presentation is effortful. The calm is maintained; the control is constructed; the stability is performed. Underneath is a sixteen-year-old boy who committed an unforgivable act and has spent thirty years trying to prove he’s someone else.

Every moment of passivity is him choosing safety over authenticity. Every deflection is him protecting the dissociation. Every moment of professional excellence is him trying to earn redemption. Every expression of love for his children is complicated by fear that he’ll damage them as his father damaged him.

Play the effort it takes to maintain the facade. Play the exhaustion of perpetual self-monitoring. Play the fear that underlies every interaction—the terror that if he relaxes control even momentarily, the monster who broke his brother’s neck will reemerge.

When Alan finally breaks at his father’s deathbed and eulogy, it’s not a single emotion—it’s thirty years of suppressed feeling erupting simultaneously. That’s not weakness. That’s what it looks like when someone finally stops running from themselves. The performance should make us understand: this man has been holding his breath for three decades. This is him finally, terribly, exhaling.